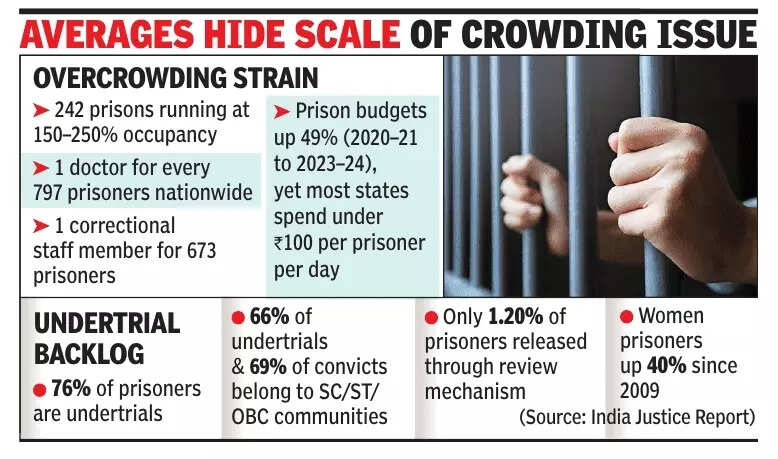

Over 300 prisons running at twice their capacity | India News

On paper, India’s prison crisis is usually flattened into neat averages. Occupancy hovers at 121%, budgets have inched up, new capacity added. The lived reality is less reassuring.In parts of the country, jails are operating without doctors, without counsellors, and with inmates left in limbo even as the barracks continue to fill.New data presented last week at a national consultation on prison overcrowding by the India Justice Report in collaboration with Prayas, a field action project of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, shows the scale of the strain. Over 300 prisons across India are running at twice their capacity, a level at which even basics like sleeping space, healthcare and supervision become difficult.The report on prison capacities cautions that state and national averages often mask ground realities. Individual jails reveal far more extreme pressure points. In Delhi’s Central Jail No. 4, overcrowding has risen steadily since 2020, reaching 550% in 2023. Danapur Sub-Jail in Bihar and Gumla district jail in Jharkhand have operated at over 300% capacity, while Kandi Sub-Jail in West Bengal peaked at 450% in 2022.The biggest reason prisons remain this crowded is not a surge in convictions, but delay. Around 76% of India’s prison population consists of undertrials, many of whom have not been found guilty of any crime. They are also spending longer periods inside. The share of undertrials jailed for three to five years has nearly doubled over the past decade, and in 2023, nearly one in four undertrials nationwide had already spent between one and three years in prison. In West Bengal, Manipur and Jammu & Kashmir, the proportion is even higher.Who stays stuck in this waiting room of justice is not random. Around two-thirds of undertrials and nearly 70% of convicts come from SC, ST or OBC communities that often have less access to legal help and fewer resources to secure bail quickly. While caste data is unavailable, the overrepresentation of marginalised communities inside prisons is telling of social inequalities.Around 30% of guarding staff posts are vacant nationwide, while 29 states have not sanctioned even a single mental health professional for prisons, despite rising stress and self-harm among inmates. Although the model prison manual mandates 1,150 psychiatrists nationwide, only 65 posts have been sanctioned and just 35 filled, leaving a policy vacuum in prison mental healthcare. Medical care is similarly stretched, with one doctor for every 797 prisoners on average and far worse ratios in some states. Karnataka and Nagaland report having no prison doctors at all, and rely instead on occasional visits from district hospitals.For Prof Vijay Raghavan, project director of Prayas (TISS), the problem lies in how prison reform is framed. “Typically when you talk of overcrowding, you say we need more space, toilets, beds… But how can we look at it from a different perspective where even if the prison capacity doesn’t increase too much, we can still have better living conditions and fewer people in our prisons,” he said, arguing that the focus must shift from building more jails to non-custodial alternatives.Around 30 NGOs at the consultation, many of them working inside prisons, said these shortages are worsened by restricted access. Human rights advocate Ajay Verma pointed out that while states like Maharashtra and Karnataka still allow social workers into prisons, many others do not. “Security concerns could be addressed through police verification rather than blanket denial,” he argued. What irks Raghavan is that religious groups are often allowed entry, while trained social workers are kept out.Verma’s teams meet prisoners regularly during mulaqat. Once trust is built, prisoners begin to talk. “Regular, sustained meetings, once every fortnight for a few focused hours, can make the difference between prolonged detention and a workable bail application,” he said.

A CSO working in Karnataka recommends creating a social and economic profile of every undertrial at the point of admission, recording family ties, housing and livelihood. When shared with courts, this data can support bail on personal bond. Southern states often show lower occupancy rates, sometimes under 100%, but the same CSOs caution that this is partly because new prisons have been built and not necessarily real reduction in incarceration.For Murali Karnam of National Academy of Legal Studies and Research, meaningful reform depends on how early civil society intervenes. “There is no point in getting a bail under trial after three months. You are expected to be there for three months in any case. But because of our intervention, we are able to get it after 15 days of arrest, that’s the hallmark of intervention,” he said, stressing on the need to strengthen prison legal aid clinics.Karnam argued that social workers are often more effective than lawyers in the early stages. “They’re able to identify multiple needs,” he said, pointing at the many undertrials who remain inside despite having bail orders simply because families are not informed or cannot navigate the system. Money alone, however, cannot solve the problem. Although prison budgets have increased in recent years, many states still spend less than Rs 100 a day on each prisoner, even as new criminal laws under the BNNS Act are expected to push numbers up further.At the consultation, Salman Azmi, member secretary of the Maharashtra State Legal Services Authority, said judges today are more sensitised to prison conditions, partly because jail visits are now institutionalised. But the real challenge, he argued, is stopping incarceration before it begins. “Many problems start at the police station. A structured pre-arrest legal aid mechanism could prevent thousands from entering overcrowded prisons in the first place.”For now, review committees meant to ease pressure have made only a small dent, with just over 1% of prisoners released nationwide, which isn’t merely a numbers problem, but one that plays out daily behind prison walls.